Stubborn Is As Stubborn Does

I share my house with five cats (a clowder, it’s called) and it’s been that way for as long as I can remember. One or two fur balls has never been enough for us. I love them, they are part of my family, but I recognize that they are stubborn, stubborn, stubborn creatures, and at times it seems like they’re the ones who run the place.

Have you ever tried to change the brand of a cat’s food, or what goes into their litter box, or even their water dish? They don’t react well to the new and different, and when they don’t react well their loud voices and sometimes unpleasant behavior can really disrupt your day.

These felines are creatures of habit, preferring a daily pattern of repeated behavior that in their view creates a safe and reassuring environment – where they feel the most comfortable. Break that pattern and you get the look, or worse. I can attest to the fact that dealing with the stubborn and the habitual can be a real trial.

In the business world, many companies are populated by managers who possess similar inflexible behavior, an aversion to breaks in pattern. Those who like things left just the way they are. Whoever coined the phrase “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” was probably a charter member in that “blinders on, head in the sand” leadership cadre who likes the comfort of repetitive action.

While it’s a truism that continuing to use yesterday’s strategy and operating principles is rarely a recipe for future success, how often do you see managers hang on to what used to work – until the signs of failure become so visible and so painful that they can no longer be accepted?

Comfort

These folks with their heads in the sand are not necessarily bad managers or even poor business leaders. What they are is comfortable, and when we’re comfortable we feel safe, relaxed in our surroundings, familiar with what needs to get done and perhaps a bit over confident about our control of the work environment.

When we feel comfortable and confident we prefer to repeat those same actions that brought us to our present state of mental ease. In other words, we don’t like to rock the boat, we don’t like what we consider “change for the sake of change,” and we’re skeptical of new and unproven techniques. We get stubborn and dig in our heels.

“It’s worked before, it brought us success. Let’s leave it alone.”

However, when someone or some event breaks that comfort level (new competition, weakened economy, technological advances, etc.), the first thing we experience is anger that our warm cocoon could be shattered by new business realities. Soon enough though, that anger will convert to a sense of fear, whether we admit it or not. More than likely we’ll act out in an aggressive fashion that disguises the panic we’re feeling.

Fear

People can be fearful of change, especially leaders. Because they don’t know the new rules, because there are risks when implementing new strategies, and those who stick their head above the crowd can get it chopped off. We’ve all seen that happen.

When you must get yourself up and out of your comfort zone it’s a natural reaction to feel defensive and unsure about what you should do next. A relaxed and comfortable leadership may not have the competencies or the experience to adapt to new business challenges. Because it’s not difficult to lead when things are going well. But when the going gets rough, when the pressure is on to change course, to implement new strategies, not so much.

“I’m not sure about what to do; everything has changed.”

Pushed from their safe environment management can find itself unsure, defensive and unsettled about the correct way forward. And until matters settle down again they can be difficult for us practitioners to work with.

You Can Help Them

You may consider managers stuck in the past as living dinosaurs, but have a care because these beasts have teeth. Because they don’t like this uncomfortable new world some will tend to shoot the messenger. In order to offer assistance to a leadership challenged by the unfamiliar, practitioners need to step up and provide steady, confident and reliable advice.

- Acknowledge the past: Yes, previous strategies have worked well and brought the company success and financial strength, reputation and a strong foundation for the future. You should acknowledge a well-deserved pat on the shoulders for management.

- Focus on the why: Whenever advocating change, focus your message, your research, your examples and your entire business case on why your recommendations lead to solutions. Keep your eye on the goal, not the changing patterns of behavior.

- Dangle the carrot: Always point toward the business and personal success that would be the result of implementing your recommendations. Besides highlighting the achievement of business success, emphasize that leadership will gain credit for managing the organization through these difficult times. Stroking the ego doesn’t hurt here.

The next time someone comes to you with an idea to build a better mousetrap, listen to them. Keep your eyes, your mind and your options open. Maybe there’s something useful here. Instead of being afraid of change, embrace the possibilities presented. New thinking that takes in the new realities surrounding you can make for a better tomorrow. Perhaps you’ll even shake off that tag of “stubborn.”

We Don’t Pay For Performance

In a recent article of mine, “Do You Really Pay For Performance?” I suggested several methods for organizations wishing to improve their Pay-For-Performance (P4P) program. On the other side of the coin, however, there are those out there who prefer to turn away from the matter entirely. Some organizations do not wish to pay for performance at all and are frankly open about it.

In a recent article of mine, “Do You Really Pay For Performance?” I suggested several methods for organizations wishing to improve their Pay-For-Performance (P4P) program. On the other side of the coin, however, there are those out there who prefer to turn away from the matter entirely. Some organizations do not wish to pay for performance at all and are frankly open about it.

While there seems to be an increasing dialogue about this strategy lately, and several recent articles have highlighted such outside-the-box thinking, current surveys suggest that only around 10% of organizations self-identify with going in a different direction for rewarding their employees. And of course, when you march to the beat of a different drum you’re going to get a lot of attention, either positive or negative. Thus the hot bed issue of late.

Marching To A Different Beat

Why does an organization argue against rewarding employees for their job performance? At first blush, it seems counterintuitive not to acknowledge how an employee performs as a helpful if not critical criteria for judging (and rewarding) that performance.

But for some, there are very real reasons for taking a different tack.

Below is a list of reasons that I’ve heard from clients of mine who have either gone down this road or given it serious thought. Maybe you’ve heard some of these yourself. Maybe you’ve heard other reasons.

- Trust: Employees don’t trust their managers to properly rate employee performance. This is a frequently heard complaint, even from those possessing a successful P4P program. The core of this comes down to the individual level (one’s own boss) and the amount of training provided to those in authority. However, when an organization feels that they need to step away from P4P for this reason, some serious self-analysis of management practices is in order.

- Everyone is great: The saying goes, all of our employees are already performing at high levels, so how can we differentiate? However, this rationale ignores the premise that standards of expected performance should rise even within successful groups. Even within high performing groups, some employees are better than others.

- One size fits all: An organization may implement a general increase where everyone gets the same pay increase. When you can’t or won’t set a policy aimed at differentiating among employees a simple alternative is to give everyone the same increase, regardless.

- Employees said so: What I heard was that the employees had told management that they didn’t want P4P. If the majority of employees are doing an average/successful/satisfactory job, wouldn’t that group be advocates for a general increase? More so the less than successful, but less so the high achievers. Another question is whether you should change such an important policy on the basis of an internal survey. Unless management doesn’t care, either way.

- EASY button: Easy to administer. It’s hard to argue that simple processes are the easiest to communicate, implement and defend against criticism. And P4P programs by their nature differentiate between employees, where losers complain and winners tend to be silent.

- Universal equity: Everybody knows how they’ll be treated. Pick a common phrase; “We’re all XYZ employees,” “Everyone puts their shoes on the same way,” or “We believe that teams, not individuals, deliver success for our organization.” The sentiment here is that the practice of differentiating between how employees are treated, especially in a [supposed] subjective manner, is inherently bad for the organization.

- Rewards for other reasons: Absent a P4P program organizations also use length of service tenure (LOS) and cost of living (vs. cost of labor) as so-called transparent reasons to grant pay increases. The price of a loaf of bread went up, thus your pay should as well. You’ve been here a long time (and we haven’t fired you), so you must be worth more money. It’s time.

Is This For You?

Maybe. Perhaps your organization has problems (above) similar to those who decided to walk away from P4P programs. Maybe your management or HR is not concerned about encouraging good employee performance.

Personally, I don’t agree with taking what I consider a drastic and unreasonable approach to rewards, and I don’t think it solves the problem, but it’s an issue that every organization grapples with, at one time or another. And there is usually more than one answer to most questions.

In my view having and maintaining an effective P4P program is hard work. It’s also work that you can’t ignore or walk away from as “Done!” You have to keep at it.

Or perhaps you can take the easy way out.

But first ask yourself; how would you like your own situation to be handled?

Do You Really Pay For Performance?

To answer this question most companies would say that, yes – they have a pay-for-performance (PFP) program. Such a statement is chic, politically correct and offers a positive message about how the company values its employees. What’s to argue with? Paying employees on the basis of what they have contributed to the company makes sense, doesn’t? If they give more they receive more.

To answer this question most companies would say that, yes – they have a pay-for-performance (PFP) program. Such a statement is chic, politically correct and offers a positive message about how the company values its employees. What’s to argue with? Paying employees on the basis of what they have contributed to the company makes sense, doesn’t? If they give more they receive more.

On the other hand, a negative response is to suggest that you’re not being fair to your employees, that your idea of a proper reward is to bypass individual performance in favor of treating everyone the same, regardless of contribution. However, as that acknowledgment would paint you as an employer who is insensitive to variations of employee effort and achievement, it’s more likely that you’ll fall in line and say “yes, of course, we pay our employees for their performance.”

But Do They? Do You?

There’s an entrenched viewpoint by many in management that granting “merit” pay increases means that their company provides pay for performance. However, if most employees receive some form of pay increase (90%+), is there really a meaningful distinction being made between high performers and those who merely occupied a chair for the past 12 months? Isn’t such a practice (if we haven’t fired you, then you’ll get an increase) more like a modified attendance award?

If you’re serious about it, your decision to adopt an effective pay-for-performance strategy should include two critical elements:

- The decision not to pay if the employee hasn’t performed

- The decision to make it worthwhile for an employee to be a high performer

One of the common pay practices that continue to hamper the effectiveness of PFP plans is the misuse of the annual merit pay pool through inflated performance evaluations and automatic increases. Continued use of this practice will increase your fixed costs, but in a manner that won’t effectively reward employee performance or encourage extra effort.

Making PFP work for your company will require hard decisions from line managers who are otherwise accustomed to maintaining employee morale through the avoidance of objective performance reviews. We have seen that, while there is a shift toward greater rewarding of individual effort, additional monies are not being provided as a result of that shift. Merit budgets will not increase to accommodate “feel good” increases. So in order to more effectively use available salary increase dollars companies need to reward their high performers with money effectively taken away from (not granted to) those performing at lower levels. You can call this, “taking from Peter (average) to pay Paul (higher performer).”

This may also mean that many average performers, the bulwark of most companies, will receive less than they might otherwise have expected from past experience (which is at least an average raise). What it comes down to is a company’s ability to afford proper rewards for their higher achieving employees (thus motivating and retaining them in the process) by reducing or eliminating rewards to those deemed as underperforming or going through the motions.

The risk exposure is that if managers, through the utilization of performance management programs, don’t properly identify and restrict awards for less deserving employees, the PFP budget will not have enough funds to afford appropriate rewards for high performers. So you should ask yourself, who is it you would rather disappoint? Who has less impact on your business and whose loss would be less disruptive to your operations?

While published reports clearly indicate a trend away from one-size-fits-all reward systems, one should look below the surface to learn whether employee performance is being appropriately measured and rewarded. That distinction is the true measure of PFP.

Getting Serious

To effectively use a pay-for-performance system a company should:

- Educate employees as to what performance will be rewarded. This requires measurements, and performance objectives that align vertically in the organization (employee goals relate to supervision, whose own goals relate to management, and on upward to corporate goals).

- Provide a well-defined rating scale that helps managers distinguish between levels of performance. Be careful of the word, “average,” as many managers use that as a default rating.

- Provide a clear distinction of reward between those who have delivered and those who have not. An employee who doesn’t see much gain from working hard all year (2%+ differential) is less likely to repeat their performance the following year. For an extra 1%, would you?

So the next time you are asked whether your company rewards employees for their performance, perhaps your answer might not differ, but now you recognize the distinction being made by your employees. It’s up to you whether to be satisfied with your answer.

Are You Too Busy?

It seems as though everyone is busy at work these days. We have more challenges to face, more complexities of the job to learn, we have to do more with fewer resources, and there just doesn’t seem to be enough hours in the day to get done what needs to get done.

It seems as though everyone is busy at work these days. We have more challenges to face, more complexities of the job to learn, we have to do more with fewer resources, and there just doesn’t seem to be enough hours in the day to get done what needs to get done.

Does this sound like you? Have I just described your typical day? I’d wager that this scenario reverberates with many managers and individual contributors out there. As a result, we’re always looking for ways to be more efficient, more effective, more focused on the task in front of us, and all without having to spend time and effort that are luxuries today.

Play It Again, Sam

Which is why I suspect that it’s so tempting to hit the “replay” button to administer our reward programs, policies, and procedures. Let’s just do the same thing again next time (work processes, project plans, program designs, time lines, etc.) because what we did worked (mainly) last time. Because we have other issues to worry about, other pressures coming to bear, so let’s stick here and now with what we’re familiar with.

The argument is compelling. You have only two hands, you have (maybe) limited help available and the ever-present tight time lines are constantly leaning over your shoulder. Likely your project book is full as well.

So a common tactic we often see is to repeat what you can, wherever you can so that there is more time left to concentrate on the new stuff. Those programs and projects that you’ve worked on before can safely become a repetitive effort. You can delegate it, you can push it to the side as you let someone else follow the path you laid out last year, and perhaps the year before. Some workflow can be placed on automatic pilot.

Perhaps that new stuff you want to/have to become engaged with is exciting, so your interests are in spending your limited time and effort there. Learning new things, perhaps gaining greater exposure with higher management, being challenged a bit more, taking in the breath of fresh air that comes with blazing new paths and gaining new experiences. New is almost always more invigorating to you as a professional, while the old stuff is just that – old. And boring.

But there lies the trap. Letting yourself ignore opportunities to improve on past practices ensures you remain captured and caged by that past. Because you feel that you don’t have the time to investigate possible improvements to something that has admittedly worked before. The mantra of, “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” came from this attitude.

The Risk Of The New Idea

However, when you don’t want to spend the time and effort to try an improved methodology – you keep on doing what you’ve always done – this causes you to miss out on opportunities to explore, invent, experiment. To grow as a professional. Taking such risks (avoiding administration and embracing creative tweaking) can pay big dividends – but you have to make the effort, even when that effort is more work than what you have on your plate now.

Perhaps you think, “What if these improvements don’t work?” You’d have spent all that time and effort, and for nothing? And now there may not be time to start again with the tried and true method. Woe is us.

That worry is another reason the pressure remains with us on to automatically repeat, to administer where you could instead innovate.

You should never be too busy to learn new skills, to push the edge of the envelope by trying out new ideas. You should never be too busy to do the right thing.

Otherwise, you’re doing little more than sitting on your hands, waiting for the clock to say 5:00.

One final thought: what was once effective and efficient eventually starts to lose that positive edge once repetition replaces innovation. So change the oil in your car before the engine fails.

Excuse To Fail

As an HR or Compensation practitioner, have you ever found yourself trying to change the mind of someone in Senior Management? When the decision-maker seems hell-bent on rushing down a particular pathway that you’re positive leads only to a cliff? From your own experience, you’re convinced that the endgame for the projected action will be negative results and also rife with unforeseen consequences. Such pending damage will land with a thud and could burn you and the organization over undue costs, damaged employee morale, increased turnover, weakened market share, litigation liabilities, etc. etc. Pick a bad reaction.

As an HR or Compensation practitioner, have you ever found yourself trying to change the mind of someone in Senior Management? When the decision-maker seems hell-bent on rushing down a particular pathway that you’re positive leads only to a cliff? From your own experience, you’re convinced that the endgame for the projected action will be negative results and also rife with unforeseen consequences. Such pending damage will land with a thud and could burn you and the organization over undue costs, damaged employee morale, increased turnover, weakened market share, litigation liabilities, etc. etc. Pick a bad reaction.

So it’s a clunker of an idea.

But the leadership has dug in their heels because they know best. And you know how low you stand in the organization chart.

We’ve talked before on these pages about various strategies to employ, if you want to, in an effort to chart a different course. I say “if” because we’ve all seen examples of those who prefer to play the political game and administer vs. lead the compensation function. Their apparent mantra is, “Keep my head down, smile, nod my head and say whatever the boss wants to hear.”

However, perhaps going with the flow is not for you. Good, but be prepared for pushback when you say, “Yes, but” to those in charge. You may find few with the stomach to discuss the merits of the plan about to be unfurled, but instead, they’ll want to reassure you over your apparent concerns about the funding. Whether you’re actually concerned or not.

It’s a red herring, a distraction.

Because I Have The Money

Have you heard this one? The reaction to whatever concerns you raise is simply that they have the money. They’ll say this to you and then consider the issue closed. It’s like them saying, “Don’t worry about it. We can afford it.” As if the availability to fund a bad idea is somehow going to turn lead into gold, to turn a bad idea into a good one.

What!?

This statement is a knee-jerk excuse used in an effort to quash an argument, as if the expense of an idea/program/policy/procedure, etc. is the sole criteria for success or failure. Tread carefully here though, because when leadership leads with this excuse, they essentially have nothing else to defend themselves. It’s like saying, ” I am who am. And I want to do this. Deal with it.” No other rationalization, explanation, justification or darn good reason is given.

You’re encouraged to check the organization chart again.

What to do? One tactic to consider using is the “There is another way” counter argument, where you first present the problems set up with by the preferred management approach, then suggest circumventing tactics that would – in the end – achieve the same result (management’s goal). Perhaps you could even save money in the process, but more importantly, you would be offering a way to gain success (their idea) with less downside (problems).

It’s Already In The Budget

This is another lame excuse that’s a close cousin to the first one. The difference, I suppose is that having the money is anticipatory, while if the money is already budgeted, well then, we’re good to go. The train has already left the station.

It’s as if to say, “No worries. We have this covered.” Again, this sort of response focuses solely on the availability of funds, not whether the idea itself – the reason for spending the money – is a good one.

Our response to this idiot cousin idea should also be similar to your earlier approach, that is, being careful not to overly criticize some senior manager’s pet idea or biased preference. There’s no need to point out the obvious flaw in their logic. Instead, you’ll need to be persuasive, not argumentative. You’ll need to project a concern that the organization succeeds, to acknowledge the valuable contributions of the (suspect) planned approach, then offer a creative alternative that still gets them where they want to go.

Dealing with the lame excuses and poor logic offered by those supposed to be leading the organization is a competency in itself. Not everyone can pull it off. You’ll need such skills to succeed where you want to manage, to direct, to lead. You won’t need it if your plan is to administer.

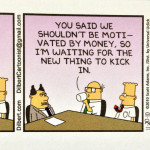

I Saw It On Dilbert

Here’s a bit of practical advice for every professional out there, whether you’re in Human Resources or frankly any functional department at all. If you see a work practice or policy highlighted in the Dilbert comic strip (a world of credit to Scott Adams), you should immediately stop that policy or practice as a bad idea.

Here’s a bit of practical advice for every professional out there, whether you’re in Human Resources or frankly any functional department at all. If you see a work practice or policy highlighted in the Dilbert comic strip (a world of credit to Scott Adams), you should immediately stop that policy or practice as a bad idea.

For the uninitiated out there, since the 1980’s Scott Adams has written about the dysfunctional workplace and its cast of oddball characters that we all recognize.

I used to work for a fellow a number of years ago who had his secretary transcribe his voice mail messages into written text. He wouldn’t listen to any of his peers/colleagues, never mind lowly little me, that such a practice was – silly/bad/impractical/inefficient/time-wasting, etc. But when he saw that same practice ridiculed on Dilbert, he stopped that very day.

The World Of Work

Who of us out there cannot identify with the experience of having to work for someone like the “pointy-haired boss?” Or the co-worker who really doesn’t do anything and always seems to get away with it?

Whether it is Wally the incessant coffee drinking slacker or Dogbert, the HR Director from Hell when these characters suggest a certain course of action I’m usually running in the opposite direction.

Because Dilbert loves to skewer the often ridiculous realities we all seem to face at work. We can readily identify with the foibles of management, laugh at the meaningless meetings and dysfunctional co-workers, then commiserate with Dilbert himself as the maligned and abused Engineer who keeps trying, day in and day out to keep his sanity in an insane world.

Entertainment

For your entertainment, I have included a few quotes from Scott Adams that relate to the workplace. You may not agree with everything he says, but he certainly seems to have his hand on the pulse of a commonly mismanaged workforce.

- “There is no idea so bad that it cannot be made to look brilliant with the proper application of fonts and color.” Add multiple pages of fluff, lots of colors, a spiral bound booklet and you have the common consultant proposal.

- “Hard work is rewarding. Taking credit for other people’s hard work is rewarding and faster.” I’ve experienced enough examples of this practice to still get angry at the memories.

- “The job isn’t done until you’ve blamed someone for the parts that went wrong.” Finger pointing is a real office skill set, where some players are notoriously Teflon-coated and never seem to face the music.

- “Be careful that what you write does not offend anybody or cause problems within the company. The safest approach is to remove all useful information.” Have you ever read an organization’s mission statement? Or almost anything written by corporate communications?

- “If you want to kill an idea without being identified as the assassin, suggest that the legal department takes a look at it.” A good technique for the passive resistor, one who spends more time killing ideas than creating them.

- “Our system requires a continuous supply of highly capable people who are so disgruntled with their jobs that they are willing to chew off their own arms to escape their bosses.” So maybe it’s true that employees quit bosses, not organizations.

- “Accept that some days you are the pigeon and some days you are the statue.” It rains on everyone. Those who are successful grab an umbrella and press on.

- “Lately…the Peter Principle has given way to the “Dilbert Principle.” The basic concept of the Dilbert Principle is that the most ineffective workers are systematically moved to the place where they can do the least damage: management.” Haven’t we all seen this? Don’t we all know someone? How/why did Bob/Sally get promoted? They must have photos from the Christmas party or some such inexplicable rationale.

So if you read that Wally or Dilbert or the pointy-haired boss are experiencing a new policy, procedure or work practice, laugh along with them even as you move your own thoughts/practices quickly in the opposite direction.

Consider these characters your “daily work alert.” They’re more accurate than the weatherman.

Is It Yes, No or Maybe?

Are you satisfied with the way your organization’s performance appraisal process is working?

Are you satisfied with the way your organization’s performance appraisal process is working?

Yes, no, or maybe?

One of the most debated issues among Human Resource professionals for the past several years has been arguments regarding effective performance appraisal processes. Everyone seems to have their oar in the water, anxious to join the debate about what works and what doesn’t.

In one corner you have the performance management crowd who want to divorce pay increases from the performance appraisal process. They prefer to focus attention on performance improvements and career counseling – issues that tend to have a longer-term focus. Looking forward, not backward. The subject of pay determination (the increase) would come later, during some vaguely defined subsequent conversation.

In another corner, you have the so-called traditional practitioners, those who tie rewards directly to the work effort and in so doing combine performance/reward determination and career counseling steps into a single conversation. Desired performance improvements and the where-are-we-going? discussion become the epilog, not the main topic.

Finally, you have the seldom reported employee perspective, those who have delivered the performance and await management’s assessment and reward determination. They expect to see a direct connection between their efforts and a subsequent reward.

What’s Wrong?

Part of the reason for such debate between opposing viewpoints is that performance appraisal systems are flawed; it’s commonly recognized that they’re the object of numerous well-deserved criticisms.

- Managers do a poor job of it: Whether it’s lack of training, lack of interest or simply an attitude of “I’ve got more important issues to deal with,” the result is often rushed, poorly thought through and . . . sloppy.

- Favored son (or daughter) treatment: The “I like you” or opposite syndrome, regardless of performance. Fair treatment can be a casualty if appraisals are too subjective. Refer again to the training issue.

- Job responsibilities not clarified: When the manager expects performance “A” and the employee thinks “B” is called for, while the outdated description shows a muddled “C” – what follows is going to be an awkward conversation.

- Forms gone wild: Human Resources and systems people always tinkering with forms, creating ever longer, more complicated processes. The usual result is a manager’s passive resistance and poorly handled assessments.

- The focal date review: “Let’s do these things all at once.” Procedures that mass produce performance appraisal forms and meetings usually result in a loss of quality – and credibility for the process. Pity the manager who has ten of these to work on at the same time.

What’s Good?

The process of performance appraisal has been around since the first manager – subordinate conversation, and that learning curve of experience has highlighted a number of advantages:

- How else are you going to tell an employee how they’re doing?

- If your compensation strategy is to have a pay-for-performance program, you’ll need performance appraisal to assess the employee’s contribution, and to somehow assign a corresponding reward — to pay . . for. . performance.

- Employees expect a connection between performance and pay. That’s what they’re listening for during the performance discussion.

- It makes sense to periodically review performance/pay levels, to eliminate the need for employees to stress over when to ask for a raise.

Practical Realities

During any performance appraisal discussion, the employee’s first question is likely going to be, “how much is my raise?” If you’re not prepared to discuss that, even mentioning your “recommendation,” you’re in trouble. Because employees tend to pay closer attention to career counseling and next steps after the raise for past performance has been resolved.

When an employee expects a performance appraisal discussion to include a reference (at least) to a likely pay raise, and you don’t cover that topic, the meeting will go rapidly downhill from there.

- They won’t be hearing your thoughts for the future, as they’ve stopped listening. You’re not talking about what they want to hear.

- Frustration and lost engagement are going to seep into body language, tone and perhaps even conversation, with the recognition that pay-for-performance is somehow not viewed as a primary concern by management (you).

- To make the assessment process work employees need to be engaged in the conversation. Otherwise what you’re left with is delivering a boring lecture to a half-interested party who only hears blah-blah-blah.

My Two Cents

Personally, I recommend connecting performance to rewards, because performance rewarded is performance repeated.

I like to acknowledge the elephant in the room, that employees want and expect that their performance appraisal meeting will cover reward determination as a key component, even if senior management approval remains pending.

I don’t like to artificially separate performance from reward as if somehow the two aren’t connected. The employee considers it a solid, direct line connection.

Arguments You Can Never Win

What’s the name of that Greek fellow from mythology, the guy forced to roll an immense boulder up a hill, only to watch it come back to hit him, repeating this action for eternity? Ah yes, Sisyphus. Today tasks that are considered futile are described as Sisyphean.

What’s the name of that Greek fellow from mythology, the guy forced to roll an immense boulder up a hill, only to watch it come back to hit him, repeating this action for eternity? Ah yes, Sisyphus. Today tasks that are considered futile are described as Sisyphean.

We may not use that term much in everyday usage anymore, but I wager that we have all experienced such a futility of effort. Frustration to the point of anger. Ever try to argue politics with someone? It’s pointless.

Lose, Lose

You can have similar frustrating experiences at work as well. No, not with politics. But in the case when an employee poses a question about their pay or their standing within the organization; a question for which you don’t have a good answer. Or at least an answer that you feel comfortable telling them. Because we all want to give good news, right? All will be well or will be soon.

But not all the time.

Here are some awkward compensation conversations that offer few popular answers.

- Job Evaluation: When an employee asks why their grade is less than someone else. They’re certain that they know all about that other job, and theirs is at least as important, if not more so. In their mind, a grade differential is just unfair.

- Pay Levels: When an employee asks why their pay is less than someone else. Like job evaluation, the aggrievement is because the questioner feels that they are worth more, and they will have plenty of emotional arguments to back up their case. In their mind, the organization is cheating them.

- Pay Progression: When an employee asks, “I’ve been here for several years, with continuous good performance reviews. So why aren’t I paid at least the midpoint of my salary range?” A worst case scenario is when the employee’s pay is actually closer to the minimum than to the midpoint.

- Merit Increase? When you are asked why an increase called “merit” seems to only match market movement and/or the COL. With a steely look in their eye, they ask what sort of recognition/thanks is involved when their pay rise seems based on anything but their personal merit.

Hiding in your office is never an effective option, as disgruntled employees will search you out and nail you with these probing questions, often at an inconvenient (even public) moment.

Dodging The Bullet

What to say? Try to strike a balance between transparency, honesty and the management line that you’re supposed to hold. It can be a tricky exercise, with success not guaranteed at all. Because sometimes an explanation isn’t going to satisfy the employee, but as straight an answer as you can give is usually a better bet.

- Job Evaluation: Most employees, in fact, do not know as much about someone else’s job. Focus your response on whether the questioner’s job has been properly reviewed. Defending the decision for another’s job rarely satisfies the complainant.

- Pay Levels: Similar to the above, focus on the questioner’s status and don’t get trapped into talking about someone else. Is the questioner paid fairly for their experience and performance? Avoid the knee-jerk “none of your business” response that you want to give.

- Pay Progression: This is a tricky one, as the facts of the matter may be exactly as the employee complains. Your reward system may have failed to maintain an employee’s value based on market growth and individual performance. You had best offer to look into the situation (and mean it). If you’re talking with a high performer the ultimate response might be a salary adjustment to keep a valued employee, while for Joe Average you’ll need to balance affordability (can’t fix everyone overnight) with a fair response. You may have to wait until the next review period to affect possible changes, but it’s likely you can only fix those employees you’re afraid to lose.

Hint: Best you check your rewards programs annually to avoid falling into this trap.

- Merit Increase? Another tricky one, as again the employee may be correct. But affordability is a real concern, even if available funds only allow increases similar to market movement and/or the COL. Emphasize the reason for the increase (performance) and the distinction with lesser performers. The amount of the increase is determined separately, for different reasons. You’d be telling the truth, though your answer is not likely to be what they want to hear.

Compensation management can be a tough job when you move away from the technical side (the numbers) and start dealing with the vagaries of employee perspectives and emotional arguments.

Good luck.

I Don’t Trust You

An often heard complaint about an organization’s performance appraisal program is that the employees don’t trust their manager to conduct a fair assessment of performance. That view is also the common response when asked why a company doesn’t use a PA or even Pay-For-Performance (P4P) program to recognize and reward employees.

An often heard complaint about an organization’s performance appraisal program is that the employees don’t trust their manager to conduct a fair assessment of performance. That view is also the common response when asked why a company doesn’t use a PA or even Pay-For-Performance (P4P) program to recognize and reward employees.

Isn’t that a sad state of affairs? I don’t trust you. I don’t trust the management of my company. What does that attitude say about your performance culture, or the state of morale or employee engagement when the workforce has such negative feelings for their leadership? How many successful organizations out there have an employee workforce that doesn’t trust them?

On the other hand, should you simply throw out the baby with the bath water – stop conducting performance appraisals – and instead dole out general pay adjustments just for showing up for work? Sort of like an attendance award. Which essentially rejects the idea that individual employee performance levels do vary, and that variance is worth recognizing and rewarding. Can you afford to treat “Super Joe” the same as “Joe Average?”

Or instead, if faced with this crisis of confidence should you take the more difficult road and make a serious effort to fix the core problem? Perhaps you should train your managers in how to properly assess employee performance. Perhaps you should hold them accountable.

Lack of trust can be an avoidable problem if you’re paying attention.

Where Managers Fail

The list below highlights the common concerns that employees are complaining about; where some managers fail to be objective. Where they can distort performance ratings, one way or another, by committing judgment errors that are based on bias, sloppiness or simply not caring enough about the process.

- Halo Effect: Generalizing ratings based on one positive achievement or strength.

- Horn Effect: Generalizing ratings based on one negative experience or weakness.

- Recency Effect: Rater emphasis on very recent event(s).

- First Impressions Effect: Generalizing later ratings based on initial impression

- Different Than Me: Giving lower ratings to those whose methods, interests, attitudes, etc. differ from yours.

- Like Me: Giving higher ratings to those whose interests, attitudes, methods, etc. are similar to yours.

- Central Tendency: Evaluating all ratees as average even when performance varies.

- Carry-Over Effect: Rating during one rating period influenced by ratings from a different period.

Likely you’ve all seen or heard of these examples. But when such abuses are left unchallenged by an organization’s leadership (all hail the status quo!) the natural result is that those on the receiving end grow to no longer trust the rater or the rating. Or the process itself.

Did I say sloppiness? When managers act as if they can’t be bothered by the performances appraisal process (too busy, better things to do, consider it a painful process, already know the answer, etc.), the resultant impact on your workforce will go beyond the ratings themselves. How long before Joe Employee says, “They don’t care about me. Why should I care about them?”

Is It Time To Kick Butt?

Small problems left unresolved will eventually morph into larger problems. Ignoring a problem that is large enough that it can alienate your workforce, disrupt employee engagement, morale and ultimately productivity, turnover and your performance culture, that is a concern that you need to address – to root out at its core. Or pay dearly for the consequences.

Managers who cannot/will not conduct proper performance appraisal reviews are not doing their job. It should be considered as simple as that. And if they are not performing such a key managerial responsibility then they should be held accountable for that lapse. Their own performance ratings and subsequent rewards should be negatively impacted. Repeated offenses should put their jobs at risk.

These people are poisoning your workforce. That should not be allowed to continue. But how often do you see a manager penalized for not properly managing their staff? It does seem sometimes that senior leadership isn’t interested, or certainly not focused on negative employee attitudes and perceptions as a cause of concern.

Employees who don’t trust their management to treat them fairly will never deliver the kind of performance, the kind of drive that will bring the organization success.

I have a prediction for you. The clamor to throw out PA programs will continue to grow and fester as long as an organization doesn’t address the core problem of delivering objective performance ratings for its employees. As long as leadership turns a blind eye to how managers assess and rate employee performance those affected employees will continue to resent what they consider a flawed and unfair system. And how motivated is a resentful employee?

You have to deal with bad managers if wish to retain/regain the trust of your employees. You leave these bad apples alone at your peril, and the cost can ruin your organization.

“I don’t trust you” is a warning sign that the Wraith of Business Failure is knocking at your door.

Are You In A State Of Denial?

Many a time I have consulted with clients who would confidently, and even smugly, brag to me that all was well with their core reward programs. “Everything is working fine,” they would say. “We may just need to update a few things.” Their view is that if anything perhaps only a few mid-course adjustments might be necessary. The source(s) of their company’s largest single expense, their payroll, are working pretty much as intended.

Many a time I have consulted with clients who would confidently, and even smugly, brag to me that all was well with their core reward programs. “Everything is working fine,” they would say. “We may just need to update a few things.” Their view is that if anything perhaps only a few mid-course adjustments might be necessary. The source(s) of their company’s largest single expense, their payroll, are working pretty much as intended.

Not much to look at here.

But in truth there often is, that there’s a mass of program rot lying just beneath the shiny veneer of their brightly colored brochures and positive messaging. If you’re only looking at surface appearances (think of that traditional iceberg picture) you could be turning a blind eye to a powerful dose of reality. Because over time even the best-conceived reward plans will go off the tracks and cease delivering the type of results that they were intended for. If you ignore them.

How long would you dare driving your car without checking the oil?

Using Wallpaper

It’s been said that you can wallpaper over the cracks in a wall, but that those fissures and imperfections would still remain – just no longer in plain sight. So who are you kidding, when you paper over faulty reward programs that once upon a time worked well? When you push that “Let’s do this again” button to once again repeat exactly what you did last year, and the years before?

A few common examples.

- Pay for performance: This is the most popular kicking boy, the P4P program. Yes, you may say that you reward for individual performance, but to be effective you should be doing more than going through the procedural motions.

- What percentage of employees receive a “merit” increase? Would 90+% raise a flag of entitlement vs. earned reward?

- What is the quality of those performance appraisal forms? Or are you simply processing paperwork by checking the box, “Received?”

- Have managers been trained to conduct proper reviews/interviews? Or are they left to their own devices, supposedly “Doing the best they can?”

- We provide competitive salaries: We hear this one all the time, to the point that this has become an almost meaningless phrase.

- Are you talking about your salary ranges or actual pay? Are you walking the talk, or simply pontificating about what could happen?

- Is your compa-ratio competitive? Are you even checking? Do you know the danger signs?

- Being “competitive” still means that 50% of the marketplace pays more than you. Can’t pat yourself on the back over that, can you?

- Our incentive plans are pay-at-risk: Do you really cut back on variable payments to management when performance slips or is at least a portion of targeted payments already baked into the books? I have seen the Finance folks “adjust” corporate results to ensure that key incentive payments weren’t negatively impacted.

Some organizations hold back on base salaries, then tout their incentive program as delivering competitive total pay. Which of course increases the pressure to deliver something in the form of additive “variable” pay.

- All employees are treated the same: It sounds good when you read phrases like this on the break room wall, but are non-managers really treated the same as managers when it comes to providing reward payments? Is your leadership assessed in the same objective fashion, or is there a greater concern that some managers/leaders might quit if their rewards were negatively impacted – by even their performance?

I’ve seen organizations who have felt no compunction about freezing or delaying regular performance reviews and merit increases for the general workforce, while at the same time would always ensure that the management cadre received regular increases.

This is not to say that various reward strategies, even some of those listed above may not be appropriate under certain circumstances. But don’t kid yourself, or worse, kid your employees. They will know when your messages are in a state of denial when compared to actions taken.

And trust is a very hard thing to regain.